From Avoidance to Action: Exposure & Response Prevention (ERP) for Anxiety Disorders, Specific Phobia, and OCD

How Anxiety Limits Life

Excessive anxiety can gradually limit the way a person lives their life, taking away their agency and replacing it with fear-driven behaviors. This is especially relevant when avoidance of fearful situations becomes habitual, as when these behaviors are consistently reinforced via momentary relief, avoidant behaviors can turn into debilitating fears. For example, someone who fears public speaking may start to avoid giving presentations or engaging in group discussions altogether. At first, they might feel momentary relief from avoiding the feared situation (i.e., public speaking). This temporary relief, as a function of avoidance, is often quite reinforcing; however, repeated avoidance has unexpected consequences, such as strengthening the feared association in the long term, making it harder to break the cycle of avoidance later on.

How Fear is Learned & Maintained

Avoidance is considered the hallmark of many anxiety disorders, including agoraphobia, social anxiety disorder, and specific phobias (Hofmann & Hay, 2018). To better understand how this occurs, it is important to first discuss how fear is acquired, as well as how it is maintained. Fear acquisition and learned avoidance are hypothesized to begin through a process called classical conditioning, most often associated with Pavlov’s dogs, whereby a neutral stimulus becomes associated with an activating event or feeling (Krypotos et al., 2015). For instance, if someone is bitten by a dog early in their life, they may begin to associate all dogs with the feeling of danger, thereby developing a fear of dogs and consequently avoiding them.

Classical conditioning fear acquisition can also extend to less straightforward examples. This can include places or settings and even physical sensations. If an individual experiences lightheadedness or muscle tightness during a stressful period of life and subsequently interprets those signals as signs of a serious medical condition, they may begin to associate any feeling of physical discomfort with potential for medical catastrophe. Similarly, if someone experiences a distressing encounter in a particular place or setting (i.e., a parking garage, alleyway, etc.), they may begin to associate related environments with danger, leading to avoidance of those locations (i.e., refusal to go to a parking garage, alleyways, etc.). Although some fear associations may seem logical (i.e., if one is bitten by a dog, they likely will not want to be around dogs), every instance whereby one avoids a fearful situation, place, or thing, reinforces the fear and compulsive avoidance through the temporary relief they feel.

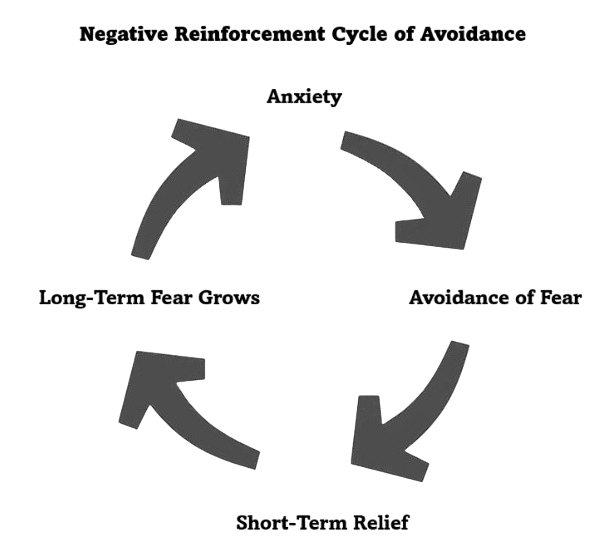

This can be further understood through the lens of operant conditioning, a foundational theory behind behaviorism, developed by B. F. Skinner, which argues that observable behaviors change as a result of consequences. From this perspective, learning occurs when a behavior is either punished or rewarded (Leeder, 2022). As such, when one engages in avoidant behaviors to feel momentary relief from fear or anxiety, they are engaging in something called negative reinforcement. In this context, negative refers to the removal of an unpleasant stimulus (i.e., anxiety) and reinforcement refers to strengthening a behavior and increasing the likelihood of repetition (i.e., avoidance). In this way, over time, the momentary relief one experiences from avoidance actually increases the likelihood that they continue to avoid anxiety-provoking situations, communicating to oneself behaviorally that their anxiety is warranted. This negative reinforcement cycle (see Figure 1 below) is emblematic of problematic avoidance and can often lead to missed opportunities, reduced confidence, and lower self-esteem.

Figure 1. Negative Reinforcement Cycle of Avoidance

Adaptive vs. Maladaptive Anxiety

It is also important to understand that not all anxiety is inherently bad. There is a reason that anxiety disorders are amongst the most common mental illnesses; to a certain extent, humans are evolutionary wired to experience anxiety. As outlined by Bateson et al. (2011), although not necessarily pleasant to experience, many symptoms of anxiety are adaptive when in response to a real threat in the environment. Some of these symptoms may include increased heart rate, restlessness, interpretation of ambiguous cues as threatening, and being easily startled.

Within each of these symptoms there is some functional significance. If one is easily startled, they are also able to quickly respond to potential threats; if one interprets most ambiguous cues as threatening, it reduces the probability of missing a potential threat; if our heart rate increases, our body is prepared for action. As you can see, anxiety, both cognitively and physiologically, does provide some adaptive benefits. However, anxiety becomes problematic when these functional components are excessive, overwhelming, and all-encompassing, thus limiting one’s engagement and agency in their life.

When anxiety and avoidance become habitual, the brain tends to generalize the experience, interpreting non-dangerous situations as threatening, potentially leading to a persistent state of hypervigilance. To exemplify this distinction, think about what would happen if you noticed a car about to hit you when walking to work or school. In this instance, it would be adaptive to get anxious and have a physical response, prompting you to get out of the way. On the other hand, it would be maladaptive to avoid all crosswalks, cars, or walking to work or school in the future because of a fear of traffic.

Exposure & Response Prevention (ERP) Therapy

Amongst the most effective treatments for anxiety disorders is exposure and response prevention (ERP). ERP is a type of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) that typically involves collaboratively working with a therapist to overcome one’s fears and anxieties through repeated exposure to them and subsequent resistance of avoidant or reassurance-seeking behaviors. ERP can include exposure to actual, real-life situations (i.e., in-vivo exposure), physical sensations associated with anxiety (i.e., interoceptive exposure), imagined situations (i.e., imaginal exposure), or even virtual-reality (i.e., VR exposure) simulations (Law & Boisseau, 2019).

As aforementioned, in addition to exposure to the feared stimuli, an equally important element of exposure therapy is response prevention. This concept refers to the act of disengaging in the previously negatively reinforcing behavior that prompts short-term relief (i.e., avoidance of a feared stimulus to decrease anxiety). As related to obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), ERP would functionally look like a patient confronting their fears related to their obsessional thoughts and subsequently resisting compulsive behaviors to feel better. For fear of spiders, this might look like observing a spider from a distance (i.e., in-vivo exposure), alongside tolerating anxiety, rather than running away (i.e., response prevention).

How ERP Therapy Works

An essential aspect of ERP is collaboratively building an exposure hierarchy, a structured list of feared situations or stimuli, ranked from least to most distressing on a scale from 1-10, with a clinician (Katerelos et al., 2008). To create an exposure hierarchy, a clinician will collaborate with their patient to first identify the stimuli that trigger significant distress (i.e., flying, dogs, spiders, etc.), and subsequently develop a ranked list of specific situations, thoughts, or feelings, that are feared and avoided (i.e., being on a plane, passing a dog park, seeing a spider, etc.). This hierarchy is then used to guide treatment in a step-by-step manner. In this way, a patient has a voice in collaboratively creating their treatment goals, engaging in treatment planning, and even in determining how to achieve those goals.

Following the creation of an exposure hierarchy, patients will systematically tackle each situation on their list with their clinician, reduce their avoidance or other relief-seeking behaviors, and re-rate their distress following each intervention. Only once a therapist and patient both agree that they are prepared to proceed to the next item do they move forward in a measured manner. Results typically show a significant decrease in fear and avoidance ratings in as little as 12-sessions (Katerelos et al., 2008). Important to this intervention is the in-between-session work that the patient completes on a daily basis. It is not sufficient to have insight into one’s fears and complete exposures once a week in-session; in order for avoidance learning to be mitigated and for a new association to be learned, daily engagement in ERP exercises is necessary. In these ways, one can see how ERP is a structured, evidence-based approach that helps individuals face their fears and break free from the cycle of avoidance.

With that being said, it is important to differentiate between the mechanisms by which ERP works via the concepts of habituation and inhibitory learning (Craske et al., 2014). Traditionally, fear reduction was hypothesized to occur through habituation, which posits that fear is gradually reduced through sustained exposures to the feared stimulus. From this perspective, repeated exposure to a feared situation, whereby one sits with their anxiety until it is naturally reduced, leads to extinction of the fear. More recently, the inhibitory learning model argued that the conditioned fear response is not actually erased by exposure therapy; rather, a new, stronger, association is built that inhibits the previous response (Craske et al., 2014).

Contemporary research tends to take a balanced approach to explaining the nature of exposure therapy from both of these lenses, whereby the benefits of ERP are maximized when patients learn new information that replaces, or inhibits, their original fear associations (Law & Boisseau, 2019). For example, if someone has a fear of cats because they were scratched by one as a child, systematic exposure to cats may not actually erase that fear; rather, it will build a new association with cats that overrides their fear. This new association (i.e., cats are cute) will then compete with the original association (i.e., cats are dangerous), ultimately leading to a more balanced perspective (i.e., even though cats can be scary, they can also be friendly).

To enhance inhibitory learning, a model known as expectancy violation has been extensively used to elicit successful results (Craske et al., 2014). This model argues that exposures designed to maximally violate expectancies of aversive outcomes are critical for new learning to occur (i.e., the more the expectancy of the feared outcome is averted, the greater the inhibitory learning). In line with this treatment model, the goal of ERP is not the elimination of fear or anxiety; instead, it is for new learning to occur. Thus, the purpose of exposures shifts from staying in the feared situation until fear declines to focusing predominantly on creating new learning experiences to overcome fear. In this way, success in ERP is defined as one’s ability to sit with and tolerate anxiety, rather than the lack of anxiety inherently. For example, if a patient comes to therapy with a tremendous fear of flying, the goal of ERP would be to tolerate flying despite their fear, not to eliminate the fear entirely nor to enjoy flying.

Challenges to ERP Therapy

While ERP is one of the most efficacious treatments for anxiety, OCD, and specific phobia, a substantial number of patients either drop out prematurely, refuse treatment, or fail to maximally benefit from it (Abramowitz, 2006). This is often due to the discomfort associated with ERP, as well as the reality that symptoms may become harder to tolerate before they get easier. Understanding this idea (i.e., facing fear is uncomfortable and scary) is pivotal to treatment success, as it is often the case that symptoms of anxiety worsen during ERP before they improve. This process can be better understood through the concepts of extinction and extinction bursts.

Extinction is the process through which the relationship between a response and consequence is terminated, leading to the absence of the response (Fisher et al., 2023). Imagine you are training a dog to stop jumping on your guests, yet every time your dog jumps on guests they positively reinforce this behavior by petting them. Over time, this behavior increases the likelihood that the dog will continue jumping on your guests. In order to extinguish this behavior (i.e., jumping on guests), the reinforcer (i.e., receiving attention, getting pet, etc.) needs to be removed. In doing so, prior to the behavior being extinguished, often times one will see a ramp up in the identified problem behavior.

In this example, your dog may jump on guests more, even if they are not receiving the same reinforcer. This is known as an extinction burst, whereby the discontinuation of the relationship between a response and a reinforcer can lead to a temporary increase in the problem behavior before it ultimately decreases (Fisher et al., 2023). Think about this way, if your dog is used to getting attention for jumping on guests, they will not immediately learn their lesson that jumping is not an effective way of getting attention, as this has been consistently reinforced over time. Instead, what is more likely to occur is that they will think they are not jumping enough to get the sought-after reward (i.e., attention). In these moments, maintaining the removal of the reinforcer (i.e., not petting the dog even when they jump more) is essential to facilitating sustained behavior change. In this way, one can see how during the process of extinction, often times problem behaviors can get worse before they get better.

Clinical Example

Given a full theoretical understanding of fear acquisition and treatment through ERP, let’s take a deeper look at a hypothetical clinical example. A 29-year-old patient with OCD reports experiencing intense anxiety and obsessions about germs, getting sick, and being unclean. As a result of their obsessive thoughts surrounding cleanliness and health, they wash their hands twenty or more times per day after touching any object they believe is contaminated. In order to address these symptoms (i.e., health obsessions and compulsive handwashing), this patient seeks out ERP therapy. After establishing rapport and building a therapeutic relationship with their clinician, the patient and therapist collaboratively build an exposure hierarchy surrounding contamination, beginning with low-tier exposures (i.e., touching a doorknob with a napkin) and building towards mid-tier (i.e., touching a doorknob directly with their hand) and high-tier (i.e., touching a subway pole directly with their hand) exposures.

Importantly, exposures to the feared stimulus (i.e., touching a contaminated object) are coupled with response prevention behaviors (i.e., refraining from handwashing), with the ultimate goal of reducing the frequency of rumination and excessive handwashing (i.e., extinction). During exposures, the patient reports experiencing a dramatic increase in their anxiety and a drop in their willingness to resist handwashing (i.e., extinction burst). However, through pairing their exposure exercises with mindfulness techniques (i.e., diaphragmatic breathing, progressive muscle relaxation, etc.) and continued response prevention, their anxiety gradually begins to subside. Over several repeated sessions and daily at-home exposure exercises, the patient’s association between touching “contaminated” objects and danger to their health weakens, ultimately leading to a reduction in their problem behaviors (i.e., obsessive thinking and compulsive handwashing), and an increase in new learning experiences (i.e., feeling contaminated is uncomfortable, but survivable), thus facilitating re-engagement in their life in a value-driven rather than fear-driven manner.

An important caveat to this clinical example, and to exposure therapy overall, is that dropping out of the exposure exercise (i.e., avoiding the feared stimulus) during an extinction burst (i.e., heightened anxiety) can have a negative impact on one’s fear association. Essentially, this would communicate to the brain, “I was right to be afraid,” or, “the danger is real,” ultimately reinforcing the avoidance behavior rather than working towards mitigating it. As such, it is essential to remember that even though one’s anxiety may get worse before it gets better in the process of ERP therapy, sticking through it is pivotal to creating lasting change.

Summary

ERP treatment can be profoundly empowering when seen through fruition. Successful completion of ERP therapy allows an individual to take back control of their life from their anxiety, rather than letting fear dictate their decisions. With support from a clinician, consistency with at-home exposure assignments, and willingness to tolerate discomfort, patients can shift from their deep-rooted patterns of avoidance to living a truly meaningful and purposeful life. Whether one’s goal is to overcome their fears or simply to stop constant reassurance-seeking from their loved ones, ERP provides a roadmap to face your fears and move forward in your life. Ultimately, exposure therapy is not about eliminating anxiety altogether, it is about making space for anxiety and learning to live life meaningfully regardless of it.

Synopsis

1. How Anxiety Limits Life

Excessive anxiety can narrow a person’s ability to engage in the present moment and in social interactions, limiting new opportunities and diminishing the enjoyment of spending time with loved ones.

Over time, consistently succumbing to anxiety can replace one’s value-driven choices with fear-driven behaviors.

Avoidance brings short-term relief, but long-term reinforcement of anxiety.

Example: Avoiding public speaking reduces anxiety momentarily but strengthens the fear of public speaking over time.

2. How Fear Is Learned & Maintained

Classical Conditioning:

Fears and/or anxious associations are formed when a neutral stimulus is paired with a threatening event.

Examples:

Getting bitten by one dog may lead to fear of all dogs.

Feeling light-headed during a stressful moment can lead to fear of all bodily sensations associated with stress.

Experiencing a distressing event in a particular setting may lead to generalized fear of similar settings.

Operant Conditioning:

Fears are maintained when they are consistently negatively reinforced.

Avoidance of anxiety-provoking stimuli negatively reinforces the fear through short-term relief (i.e., removal of the unpleasant feeling).

This leads to a cycle of avoidance, whereby anxiety prompts avoidant behaviors, leading to short-term relief, long-term fear growth, and thereby continued future anxiety.

To break the cycle, one needs to face their fear as well as stop engaging in negative reinforcement (i.e., avoidance).

3. Adaptive vs. Maladaptive Anxiety

Anxiety is not always bad; it has evolutionary benefits as well, such as heightened awareness and rapid response time to danger.

Anxiety becomes pathological when it is excessive, generalized, and restrictive to one’s life, which can at times lead to a state of constant hypervigilance.

Example: Feeling anxious and getting out of the way of a speeding car is adaptive, whereas feeling anxious and avoiding all streets, cars, or crosswalks is excessive.

4. Exposure & Response Prevention (ERP) Therapy

ERP is an evidence-based treatment for anxiety disorders, OCD, and phobias.

Exposure: behaviorally and cognitively facing feared situations, sensations, and/or thoughts.

Response Prevention: resisting avoidant behaviors, compulsions, and/or reassurance-seeking.

Types of Exposures:

In-vivo: Exposure to real-life situations (i.e., dogs, public speaking, etc.).

Interoceptive: Exposure to feared bodily sensations (i.e., light-headedness, racing heart rate, hyperventilation, etc.).

Imaginal: Mental exposure to feared scenarios (i.e., imagining a feared scenario cognitively).

Virtual Reality (VR): Exposure to any of the above by utilizing a VR headset to simulate these environments and/or imagery (i.e., VR of an airplane, dog park, etc.).

5. How ERP Therapy Works

Habituation: Repeated exposures to the feared stimulus, paired with response prevention, leads to distress naturally fading over time.

Inhibitory Learning: Fear associations are not fully erased; rather, they are outcompeted by stronger, new learning experiences.

Goal of ERP: To build tolerance, resilience, and allow for new learning opportunities, not to eliminate fear and anxiety entirely (i.e., “I can handle this, even if I feel anxious”).

6. Challenges to ERP Therapy

Many patients drop out of ERP due to the discomfort of confronting their fears.

Symptoms may get worse before they improve due to the nature of the therapy.

Extinction Bursts: When a previously reinforced behavior that facilitated momentary relief (i.e., avoidance) is no longer utilized, one’s anxiety may temporarily intensify.

Pitfall: If a patient discontinues ERP during an extinction burst, it may strengthen the original fear association rather than create a new learning opportunity.

Example:

Someone’s dog often jumps on it’s owner to get their attention.

The owner stops giving the dog the attention it seeks whenever he jumps, hoping that the dog will eventually stop jumping.

Rather than immediately learning that jumping no longer will get their owner’s attention, the dog may temporarily start jumping more to get the attention they seek.

If the owner gives in to these repeated attempts, it will make the dog more likely to jump in the future.

If the owner resists these attempts, the dog will eventually learn that jumping is not an effective way to get attention.

7. Clinical Example

A 29-year-old patient fears contamination and being unclean, so they compulsively wash their hands multiple times an hour.

Through creation of an exposure hierarchy, the patient systematically tackles each of their fears (i.e., touching a doorknob, touching a subway pole, etc.) while simultaneously engaging in response prevention (i.e., not washing their hands immediately afterwards).

Their anxiety may spike at first (i.e., extinction burst) in response to a lack of the negatively reinforcing behavior (i.e., handwashing).

With repeated daily exposures, distress decreases and their beliefs around contamination gradually begin to shift.

Fear-based behaviors weaken with the less power they give them, and subsequent engagement in daily life becomes more value-driven rather than anxiety-driven.

8. Overall Summary

ERP empowers patients to reclaim agency in their lives from their anxiety.

With clinical support from a therapist, structured practice, and willingness to face one’s fears, individuals can:

Reduce their avoidance.

Stop compulsive reassurance-seeking, compulsions, and/or rituals.

Live a meaningful life despite anxiety.

Ultimately, ERP is not about eliminating anxiety – it’s about building resilience and freedom even in the presence of anxiety.